With this omnibus post, I am bringing this blog right up to date. What an achievement!

Since Pat and Helen left, exactly a week ago, Karen and I have kept active, but haven’t

done much in the way of tourist-y things. The one big exception was a visit to

the Basilica of Santa Maria de la Victoria, which we did the day the ladies left. It

will be a highlight of our time in Málaga.

The Basilica is off the beaten

tourist track. Karen found mention of it far down a list of things to see and

do in the city, even though it came highly recommended by those who reviewed it –

4.5 stars out of five on TripAdvisor. It’s in a part of town not often visited

by tourists.

When we arrived at the large,

unassuming-looking church, we went straight in and began looking around. I was

thinking it wasn’t particularly impressive when a fellow came in and spoke to

us in Spanish. When I explained that we didn’t understand Spanish well, he apologized

and immediately switched to English. This was Miguel Angel Pérez, the Basilica’s

volunteer guide. Did we want a tour of the crypt and altar? Because if we did,

we’d have to come with him now as the church was closing soon. (Yet another

case of having wrong information about opening times! We had thought it was

open until 14:00.)

Miguel is absolutely passionate

about the place. A good part of his spiel was taken up with complaining bitterly

about the lack of attention the Basilica receives from the city’s tourism

powers that be. He’d finish one of these little diatribes with,

“In-CRED-i-bool!” or “I’s TERR-i-bool!” The result, he says, is that visitors

are few, and the diocese might have to discontinue the tours. I took this as

softening us for a request for donation, but that wasn’t it. He genuinely wants

people to know about this place and come to it.

The story behind it is interesting.

The Basilica was administered by the Minim order of monks, founded by the

Italian Saint Francis of Paola in the 15th century. When the original 17th

century sanctuary and crypt were destroyed in the 18th century, the Count of

Buenavista – whose Renaissance palace now houses the Picasso museum – stepped

forward and said he would pay for reconstruction, on the condition that he and

his wife could be buried in this holiest of places. The Minims agreed, but negotiated

complete control of design.

The result is a unique

masterpiece of rococo plaster carving. The crypt is a small, low-ceilinged room

with the duke’s and duchess’s tombs along one side, kneeling effigies facing

each other. The walls on all four sides are encrusted floor to ceiling with white

relief carvings of skeletons and other symbols of death, on a black ground. For

the Minims, Miguel told us, the crypt represented the earthly realm and the

symbolism was intended to remind viewers of the inevitability of death and the

need for contrition and virtuous living.

Miguel admitted us to the crypt

through a half-open door, in darkness, then with a great flourish, turned on

the floodlights. He was like a kid showing off his favourite toy. He directed

me where to stand to get the optimum photo and told me to take my time shooting.

He later urged us to post a review and the photos on TripAdvisor as this was

the best way the Basilica could hope to attract more visitors.

If the crypt is the earthly

realm, Miguel explained, then the sanctuary behind the altar – where he took us

next – is the heavenly. In the centre of it sits a statue of the Virgin that

had been sent to Málaga as a gift by an Austrian prince to commemorate the

re-conquest of the city in 1487. It’s over 500 years old. The walls and ceiling

of the dome above it are decorated with plaster relief carvings, gilded and

coloured, leading the eye up to heaven. As Miguel might say, “In-CRED-i-bool!”

The next day, the Friday, we

walked to the church that we can see poking up over the buildings on our block,

the parish church of San Felipe Neri. It turns out to be quite a pretty one on

the outside, with lovely geometric painted walls. We didn’t go inside, but may

later. Our destination this morning was the Museum of Flamenco Art, just off

Calle Beatas, about 10 minutes from the flat. The place is run by the Peña Juan

Breva, a foundation for promoting flamenco in Málaga. Juan Breva (1844-1918), a

singer and guitarist, was an iconic figure in the history of Malegueno

flamenco.

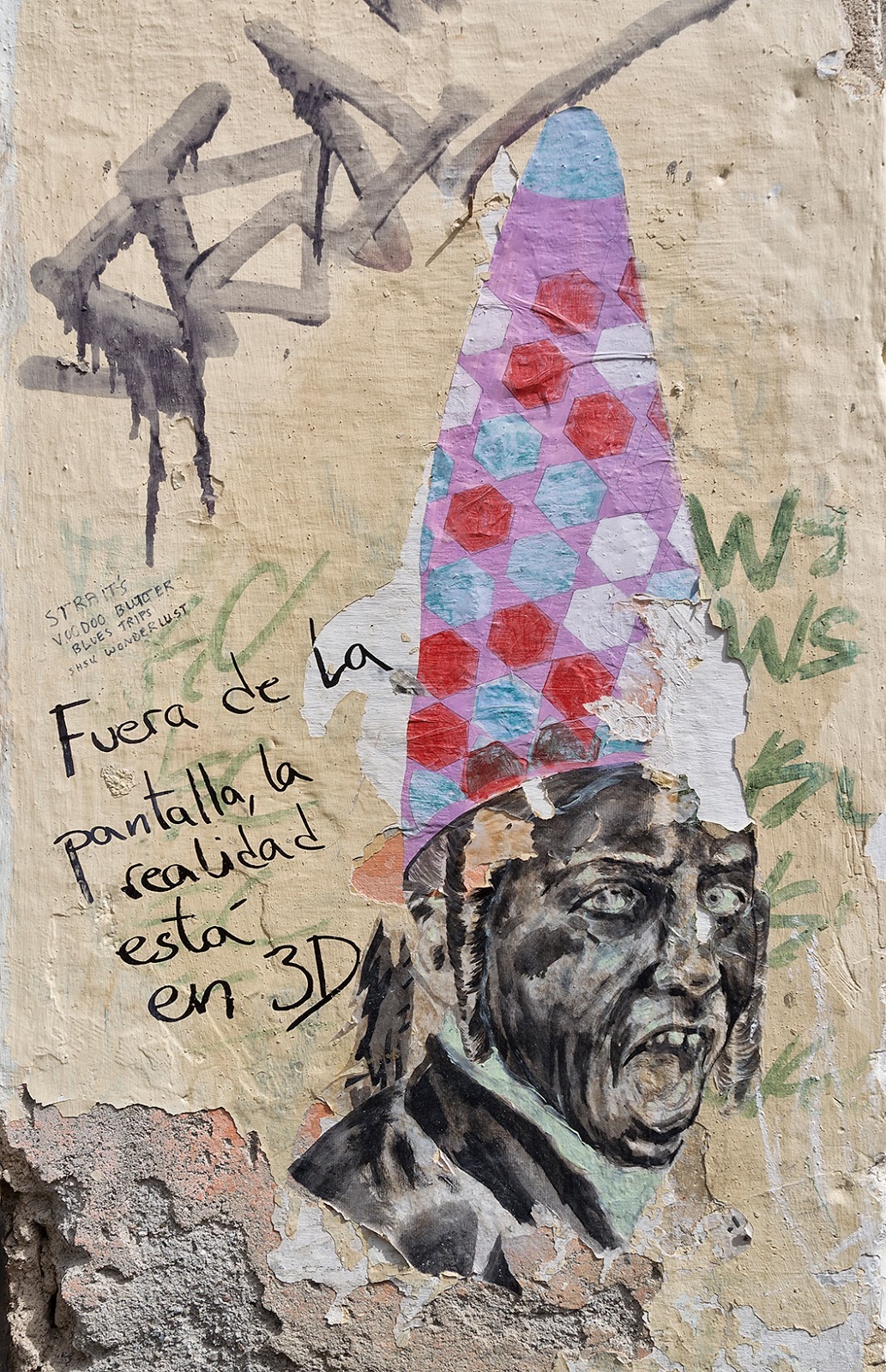

|

| Spotted near Church of San Felipe Neri |

|

| Church of San Felipe Neri |

The place also houses a tapas

bar where they have well reviewed flamenco performances, and some kind of

archive, which includes, among other things, an important collection of

hundreds of old flamenco phonograph records. When we came in, there were a

couple of old guys sitting in the bar, sipping their carajillos (coffees with a shot) and chatting. They were very

friendly and urged us to come back later for a performance.

The museum itself, spread over

two floors, is not really professionally mounted, but has charm. It includes a

hodge-podge of original and reproduction flamenco dresses and other performing paraphernalia,

old guitars, photos and, true to the museum’s name, art inspired by the music,

none of it very distinguished. The labels are in Spanish only, so we didn’t get

a lot of it. Still, it was mildly diverting to look at the artifacts, and the

admission was only €1 apiece. Maybe we’ll go back for a performance.

We meandered around the old

town for awhile, collecting street art photos, and then went home. I don’t think we did much else that day.

On Saturday, we were feeling

our oats apparently. We decided to walk again out to Pedregalejo, the former

fishing village on the northeastern edge of the city. Our idea was to walk

along the beach promenade there. The first time we went, we stopped at the

beginning of the promenade. We’d go further this time, have lunch at some

point, then walk – or bus, or cab – back. It was a lovely sunny, warm day,

forecast to go up to 24C.

The walk to the edge of

Pedregalejo is nice enough, with beach and sea views on the right, but also

traffic noise and whizzing cars on the N340 alongside. When we got to the

village, we turned down to the beach, which is a few blocks in from the

highway. The promenade is lined with restaurants, bars, seaside cottages and

fishermen’s houses. It goes much, much further than we imagined.

|

| Pedregalejo |

|

| Pedregalejo and Malaga skyline beyond |

We walked another almost four

kilometers through El Palo and El Candado, two other suburban beach communities.

In El Palo, we passed through a very busy street market, selling mostly clothes

and knick-knacks, but also some fresh produce. The restaurants were all set up

for lunch and starting to fill. The beach restaurants along this stretch of

coast set up fire pits, usually in old aluminum row boats, and cook fish,

especially sardines, on skewers over an open wood fire – an Andalusian bbq. Sardines

on a skewer is one of the iconic images of the region. A street artist we see

every day near the Roman Theatre in Málaga sells almost nothing but little

paintings of skewered sardines. To each his own...

At El Candado, the promenade

rejoins the highway. We turned back there. We had been hoping to get a close-up

look at a tower we could see in the distance from the city. It looks like a

modern highrise or office tower, but with unusual protruberances on the side.

It stands on its own on a hilly point. We’d keep looking at it, saying, “What the

hell IS that?” It had become an obsession. Now, although we must have been very

close to it, we couldn’t see it at all, presumably because we were too close to

a rise in the land that hid it. We’ll have to drive out there when we rent a

car next week.

We stopped at Restaurante Antonio,

a big place right on the promenade in El Candado, one of the few that

advertised it served meat dishes – which we of course required. Lunch was, let

us say, an experience.

It felt like being on the set

of one of those 1970s films about village life in southern Europe – Zorba the Greek, or something like that

– only updated to 2017. We knew weekend lunch out was a big deal in Spain. It’s

a time for family to get together. The restaurants are jammed. Sunday is the

traditional day, but Saturday is evidently just as big, perhaps especially on a

sunny spring market day at the beach.

We were surrounded by families

at Restaurante Antonio. At a long row of tables to my right was a huge extended

family with at least three generations. I counted four brothers – same banana nose

on every one of them – aged late twenties to late thirties, each with a pretty

wife and small children. They arrived separately over a 20-minute span, each

arrival setting off a marathon of cheek kissing and loud greetings. In the end,

there must have been over 25 people at the table.

There is no apparent

self-consciousness about being out in public here. Families behave at a

restaurant as we would in the privacy of our back yards. The kids were running

up and down the promenade, kicking footballs, skateboarding, scootering. Or out

on the beach, running or digging in the sand. A parent might occasionally

remonstrate with an unruly child or be called on to soothe an injured

or unhappy one, but nobody seemed to mind the kids running free. It was

expected. More than once, I saw kids run in front of or fall in front of

strangers walking along the clogged promenade. The adult would smile and reach

down absently to pat the child while continuing their conversation, and walking

on without pausing. Nobody minded. And for the most part, the kids were not badly

behaved, just exuberant.

At the table on the other side of

us, which was practically out in the flow of the promenade traffic, sat a

young couple in their early thirties, a taciturn-looking, heavy-set fellow and

his slender, elegant wife in movie star sunglases. They had three kids, two

boys aged about eight and six, both dressed in football outfits with UNICEF as

the team logo – don’t know what that’s about – and a little girl, maybe two,

toddling around on stubby legs, smiling at everything. The kids rarely sat

still, and apparently weren’t required to. If they felt like going off and

playing, they did.

At one point, the mother,

obviously the tough-love parent, with a voice like a drill sergeant, frog-marched

the oldest boy away from the table after some infraction or other – teasing his

little brother, I think – and spoke to him sternly. He was a bit subdued for

awhile after that. The parents would change places at the table as

child-minding duties required. The father sat cradling the toddler, feeding her

for a long while. The mother would stand and walk around the table to cut food

for the children or get them to sit straight. While the foot traffic flowed by

two steps away.

It was tremendously

entertaining. Meanwhile, the smiling waiters were moving among the tables. The

cookers at the fire would hustle up from the beach with a plate of skewered

something-or-other. The food was rarely served all at once. The dishes came one

by one and appeared to be for sharing.

And then there were the African

craft and sunglasses sellers, wending among the tables. They’re all over

southern Europe: tall, thin, dark-skinned men in sunglasses and dreadlocks. The

same ones kept returning and offering their wares as the tables filled around

us. Nobody appeared to mind. At the table behind me, a young woman sitting

with her husband or boy friend, engaged with one of them. They had a smiling conversation,

but she bought nothing. (I’m not sure I’ve ever seen anyone buy anything from

these guys.)

At one point, I caught an odd

little interplay at the restaurant next to Antonio’s. The eight-year-old from

the table beside us was sitting on his skateboard, absently rolling it back and

forth – this is probably thirty feet from his family’s table. One of the African

sellers, who was on his second or third pass through, leaned down and held out

one of his trinkets to the kid, as if offering it to him. The kid looked up at

him, like, “What?” When he finally reached out his hand, the African guy pulled

the trinket away, smirking. The kid couldn’t care less, just stared after him

in slight puzzlement.

The Africans weren’t the only

peddlars. There were also Spaniards selling lottery tickets. They have little

machines on their belts, like the ticket sellers on London buses in the old

days. I’m not sure I’ve ever seen them sell anything either. Karen was amused

by the couple selling packaged sweet buns table to table. “This is a restaurant for heaven's sake!”

She was offended on behalf of Antonio who might be missing out on

a dessert sale. But the restaurant tables were on the public promenade, so

Antonio probably didn’t have private-property rights here.

Our lunch? Dreadful. Pork chops

with fries, a shared mixed salad to start. To be fair, the salad was fine, a generous

serving, as always, and fresh ingredients. The fries with the chops were good

too. It’s just that a couple of the pork chops were over-cooked almost to to

the point of incineration. This is what you get, I suppose, ordering

meat at a fish restaurant where they cook over an open wood fire. It didn’t

matter. The beer and wine were good, and the entertainment top notch.

|

| Restaurante Antonio: that's the eight-year-old from the next table on the promenade |

We walked back along the

promenade, unspooling the day. The restaurants were full. The sun continued to

shine. We probably had way too much sun this day – and me without sunblock! The

market was tearing down when we went by again. I had thought we might take the

bus back to the city, but we ended up walking all the way. It must have been

close to 20 kilometers in the end – over 25,000 steps on Karen’s FitBit.

|

| Pedregalejo |

That night, Karen started

complaining of a cold coming on. The next day, she thought she still had energy

for another long walk, but really didn’t.

We went anyway – the other direction this time: west and south. We walked through town, as we’d been along the seafront

– through not very interesting commercial docklands – on a walk with Shelley

a couple of weeks before. We took Avenida de Andalucía, a grand boulevard lined with rich-looking modern highrises and office towers. Across the street, we

could see the Jardín de Picasso, which looked lush and pretty, but was

inaccessible across several lanes of traffic.

It’s deceptive how far away from

the water we’d come taking this route. The shore line curves away. The walk

down along Avenida de Juan XXIII, an even more boring and noisy major artery,

was much longer than we expected. We arrived at the sea tired, hot and

footsore. The promenade was jammed with strolling families, the beach carpeted

with sunbathers – which was surprising, as it would be mostly locals here, not

tourists; this was the suburbs. In Valencia at this time of year, even on a

warm sunny day like this, it would mostly be tourists sunbathing. The locals

would be walking along the promenade in their Sunday finery, or filling the

restaurants.

We sat on a park bench for

awhile, watching the people, then trudged wearily home. I took one picture, of

the beach and the commercial port beyond. Karen accused me of taking it only because

of the nude sunbathers, but I hadn’t even noticed them until we walked on and

drew alongside them. (If you click on the picture to enlarge it, you might just be able to make them out.)

Karen’s cold was now in full

flower. Our activities over the next few days would be much curtailed. We

mostly went for walks around the nearby historic centre.

On Monday, we did walk down to

the harbour. We sat in the sun and read our books for an hour – or Karen did; I finished mine after ten minutes and went off exploring. At five (when things start to open again after siesta), we went in search of a little

art gallery we'd heard about, run by the Fundación Unicaja. Unicaja – you-knee-CAH-hah - is one

of the big banks in Spain. Like some other banks here, it invests in

cultural activities – concerts, gallery exhibits, etc. – as a form of self-promotion

and philanthropy. We enjoyed several excellent shows at the Valencia gallery run by Bancaja’s

similar foundation.

This one was difficult to find.

It’s not in the same location as the foundation’s Málaga business offices,

which is where Google maps wanted to send us. I asked about it at a tourist office

and was directed to the same place. Did the young woman not wonder why a

foreign tourist would want to find business offices of a bank cultural

foundation? A young woman in one of the bank’s nearby retail outlets also

directed us to the same office. C’mon people! That’s not what I want! We

circumnavigated the building it was supposed to be in, twice, peered at the directories

on two doors but saw no sign of the foundation. Frustrating.

In the end, more or less by chance,

we stumbled on the right place. It's in Plaza Siglo, about ten minutes from home,

tucked upstairs in one of the bank’s retail branches. We knew about the place

because I’d seen a poster for an upcoming exhibit. I realized now that I had

seen the poster in this very square, with an arrow pointing to the gallery entrance.

Doh!

The exhibit we’d spent so

much time and energy locating was Frida

Kahlo: la vida como obra de arte – Frida Kahlo: Life as a Work of Art, paintings

by Fausto Velázquez. Velázquez is an artist of about our age who had been an art

teacher before retirement. He apparently has or had an obsession with the early-20th

century Mexican painter Frida Kahlo. One could argue that her artistic career was

summed up by the title of this exhibit. Velázquez has painted 20 or 30

reinterpretations of Kahlo’s famous self-portraits, in his own much more rigidly

realistic style, with different lighting and backgrounds. Frida often

looks much prettier than she did in her own paintings. It was mildly

interesting, but after awhile, the pictures ran together. Stop! Too

much Frida! And the show brochure, in Spanish and English, failed to

satisfactorily explain why Velázquez had embarked on this exhaustive series of paintings.

On Tuesday, we tried to visit

the Museum of Semana Santa (Holy Week). As in Seville (but not Valencia so much),

Holy Week is a huge deal in Málaga. We’ll still be in the city for the first day, Palm

Sunday, when the processions of effigies by various hermanedads, or religious

brotherhoods, begin. So we thought it might be useful to get some background.

The place was difficult to find, even though only a few minutes from home and,

when we did find it, unaccountably closed – despite the sign on the door

clearly indicating it should have been open. What is it about this city and

museum opening hours?

On that same walk, I tried yet

again to find what I’ve come to refer to as “the square of the violin maker,”

an almost mythical place that I stumbled on while running one day early on in our visit, but could never

find again. I tried to take Pat and Helen to see it, and Karen and I have halfheartedly

searched for it a couple of times. It was an interesting little triangular

plaza tucked away down an alley. The main feature for me was the luthier’s

studio – with the luthier working in the window. There were also some interesting

little shops.

It wasn’t anything really

wonderful, it just bugged me that I couldn’t find it again. We couldn’t find it

this day either, or not at first. I finally sent Karen home to rest, determined

to stay out and take some photographs – and maybe find the square. I walked a

half block from where I'd left Karen, and there it was. A myth no

longer.

I also went down another little

alleyway we’d often passed to a place that had looked like a restaurant with a

courtyard patio. It’s actually a social and cultural “club.” There is a

courtyard, very pretty, with a bar, tables, wall murals and a fountain. It did

not appear to be an exclusive, members-only kind of club. Nobody stopped me

coming in or asked me to leave or to stop taking pictures.

I have also been taking

pictures of building fronts in the historic centre. We are both very taken with

the curved-front buildings with bow windows or balconies, often painted in

pastel shades. They date, I think, from the 19th century, possibly 18th in some

cases.

On Wednesday, we went for a

longer walk, almost down to the port. Karen had had a bad night with her cold,

but was determined to get some exercise. The sun was shining, but it was cooler

than it has been – mid-teens Celsius. We picked our way along, choosing the

sunniest streets to stay warm. Amazing how quickly you get accustomed to warmer

temperatures and adjust your idea of what constitutes cold. I tried on a pair

of green suede shoes in one shop just up from Alameda Principal but they didn’t

have my size. Too bad. Nice shoes at a good price.

Today – my god, I’m almost

caught up – we went out in the late morning to visit a highly-recommended

church, the Iglesia de los Santos Mártires (Church of the Holy

Martyrs). It's not far from the flat, but we meandered as usual, and stopped a couple of times for photos, once in a flamenca shop on Calle Carretería. There are a few of them around the city, shops selling flamenco-inspired dresses: tight bodices, flared and/or ruffled necklines and hemlines. Very colourful. I think they're sold mainly for ladies, and little girls, to wear at the Feria in the summer, the other big festival here after Semana Santa.

The Church of the Holy Martyrs is gorgeous. It was one of four built in the old city right after the reconquest, with money from the Spanish royals. There are apparently four brotherhoods attached to this church, which may explain why it has the money to decorate with such opulence and build all the equally opulent side chapels. We spent a half hour, goggling at

the richness, and snapping pictures.

On

the way home, we went down the street where the Museum of Holy Week is supposed

to be. It was open – or part of it was open, a special exhibit of contemporary

religious paintings by José Antonio Jiménez Muñoz. He specializes in paintings to be used in posters advertising Semana Santa around Spain. He’s a talented painter, but really needs to find some new subject

matter.

In the afternoon, we went out for another walk, down to the harbour and back up through the historic centre. Same old, same old. I think it's almost time we rented a car and got out of town.